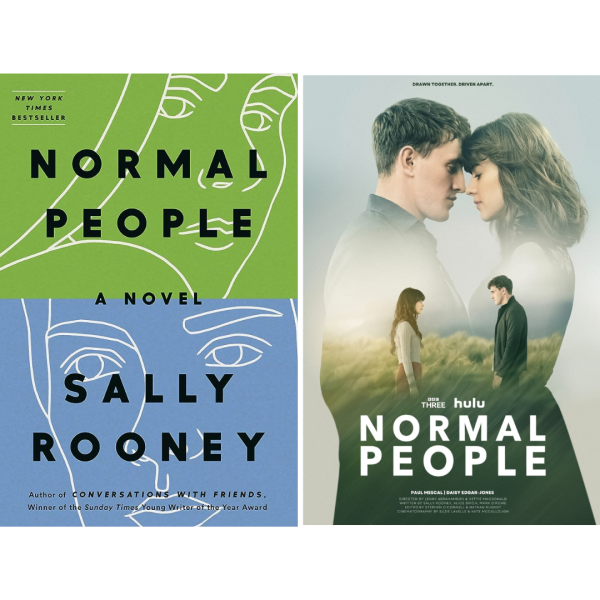

#1- Normal People

In high school, Connell Waldron is a popular and highly intelligent student who begins a relationship with the unpopular, intimidating, and equally intelligent Marianne Sheridan, whose mother employs Connell’s mother as a cleaner. When they begin an affair-like relationship, Connell keeps it a secret out of shame, leading to the demise of the pairing. Fast-forward to them attending the same college, Marianne blossoms at university, becoming pretty and popular, while Connell struggles for the first time in his life to fit in. The two reconcile, starting a complicated, years-long love story that exposes their traumas and insecurities.

If you have read Salley Rooney’s Normal People, then you would know it is not a particularly easy book to adapt. It is primarily character-driven, meaning that character development supersedes plot development. This characteristic of the story provided an interesting challenge for screenwriters: how do you take a book built around two characters prone to internal monologues and make it rewarding to watch? The 12-part TV show does this with a few methods.

The issue with adapting books onto the screen is that it usually loses out on important inner monologues that these characters have. In Normal People, we have pivotal moments in the book conveyed through streams of consciousness, such as Connell unveiling a life-long sense of alienation to his therapist, or Marianne coming to terms with the sense of control Connell had over her in their high school years. As such, the essence of Normal People is not in the plot, but rather in the characters. Usually, these types of internal monologues are translated into a voiceover form, but these do not always work. Rooney’s writing in Normal People is purposefully simple and stripped-back; it makes readers feel like they are in the story, experiencing everything as Connell and Marianne do. Voiceovers would take away from this effect. In the TV show, the screenwriters opted to convert some of these thoughts into dialogues and conversations that push the plot forward in a similar manner.

The screenwriters also did something unique by utilizing silent scenes where there is no conversation to encapsulate the characters’ thoughts. One would think this would bore viewers, but instead these silent stretches allow the viewers to immerse themselves, by forcing viewers to imagine the thoughts the characters could be having.

Finally, the show transforms the tone of the entire novel. Rooney’s writing style is characterized by her snarky humor, wit, and sarcasm that sets her apart from her contemporaries. In Normal People, this tone juxtaposes the tragedy and calamity that is Connell and Marianne’s relationship. The adaptation opts for a more depressing and bleak tone displayed through the soundtrack, presence of muted colors, and the actors’ portrayals of the characters. Of course, preferring the show’s tone is an entirely personal preference, but I believe this choice communicates the themes of how miscommunication and insecurity result in the pitfalls of relationships much more vividly, leaving viewers reeling, even after the final episode.

#2- Anne With an E

First published in 1908, Lucy Maud Montgomery’s Anne of Green Gables has seen its fair share of adaptations. A staple of my childhood, I have also watched a fair share of the book’s adaptations. When you have seen so many adaptations of the same material, they start to feel recycled and old. Then, something like Anne With an E comes along.

The original Anne of Green Gables sets us with Anne Shirley, a young orphan mistakenly sent to middle-aged siblings, Marilla and Matthew Cuthbert, looking to adopt a boy to help out with their farm. At first, Marilla is adamant about sending her back, but with Matthew’s encouragement, and her growing fondness for Anne, Marilla decides to let her stay. A series of adventures ensues as Anne navigates the struggles and joys of settling in Avonlea, her friendship with Diana Barry, and a one-sided rivalry with her classmate, and future love, Gilbert Blythe.

Each of these deviations allows the show to modernize and convey themes that are relevant to current-day society. Season two explores homophobia through the addition of a new character: Cole Mackenzie, a closeted classmate of Anne’s who is forced to deal with bullying for displaying more “feminine” qualities. New plot lines are mixed in too, such as Gilbert Blythe finding a job on a ship that causes him to end up in Trinidad. Here, he meets more new characters, like Sebastian “Bash” Lacroix, a Trinidadian man who ventures back to Avonlea with Gilbert. In Avonlea, Anne With an E successfully provides racial commentary through the interactions and experiences Bash has with Avonlea’s white villagers. In season three, feminism becomes a primary theme when the plot delves into topics of sexual abuse and the subordination women have often been subjected to. Alongside feminism, this season also chooses to address North America’s dark history with indigenous peoples through Ka’kwet, an indigenous girl that Anne befriends, who is subjected to attending a residential school. Each divergence from the original plot feels new and refreshing, setting this adaptation apart from its counterparts.

Yet, despite the new presence of darker themes, the overall tone of the show remains the same as the original: lively and heart-warming. We still get to watch Anne participate in her disastrous episodes, such as getting Diana drunk by serving her currant wine instead of raspberry cordial, or dying her hair green in an attempt to make her red hair black. Of course, we also get to watch Anne’s rivals-to-lovers relationship with Gilbert develop throughout the entire show.

Anne With an E perfectly balances staying true to, and honoring, the original source material, while also creating new aspects that allow fans of the original books a refreshing viewing experience.

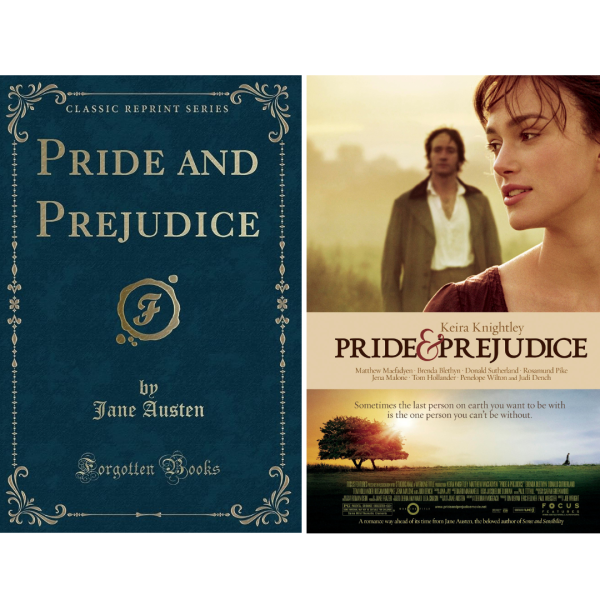

#3- Pride and Prejudice (2005)

Visually stunning with its beautiful shots and the powerful performances of its actors, Joe Wright’s 2005 adaptation of Pride and Prejudice transports its viewers to the beginning of the 19th century when the tumultuous romance between Mr. Darcy and Elizabeth Bennet began.

While Pride and Prejudice has seen its fair share of on-screen adaptations, only the 2005 version provides a fresh take on the centuries-old story, while also staying true to the original source material by Jane Austen.

Perhaps one of the most notable differences between the movie and book is the protagonist herself. Pride and Prejudice’s Elizabeth Bennet has long been hailed as a byproduct of the novel’s feminist themes, yet her feminist ideals and character are further emphasized in Keira Knightley’s portrayal of Elizabeth as feistier and much more impassioned than the book. This interpretation emphasizes the independence Elizabeth has outside of the societal expectations regarding marriage and female autonomy that were placed on the women of her time. However, this is not the feminist sentiment that I found myself appreciating; the one I appreciated was at the very end.

The movie cuts out minor characters, and heavily condenses subplots, putting a stronger focus on Elizabeth and Mr. Darcy’s romance. Nowadays, I feel that many hold a narrow scope of what it means to be a feminist. In the media, feminist characters are women portrayed as confident and capable, successful in their careers, working for no one but themselves, prioritizing ambition over love. Women who do dream of finding love are thought to be antithetical to feminism. Pride and Prejudice provides us with a female protagonist that is determined, strong-willed, and self-sufficient, yet simultaneously is able to experience a beautiful romance and not lose herself in the process, a feature uniquely emphasized in the 2005 adaptation.