INTRODUCTION

People have always consumed life’s necessities– food, water, shelter– but there was a sudden shift that occurred in the late 1800s. Fueled by a second wave of rapid industrialization and economic growth, a new consumer culture emerged during the Gilded Age. It was characterized by the increase of disposable income, department stores, mail-order catalogs, and new forms of advertising. The frugality of the past had been left behind, and such compulsions only grew. By the mid-1900s, the average American’s role as a consumer was solidified, according to The MIT Press Reader. This consumer culture carried over into the 21st century, forming the one we know today.

The money that we spend often acts as a powerful expression of identity and innovation nowadays, according to Brookings, a non-profit public policy organization. Our current state of consumerism allows us to enjoy a life that is not limited to simple bare necessities.

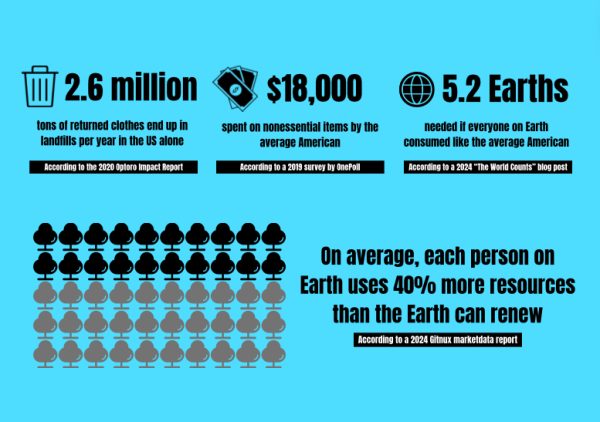

However, despite such benefits, more attention is being drawn to the line between “consumption” and “overconsumption.” What do we do when millions of tons of clothing Americans throw out to make room for the new ones are amassed in landfills? What do we do when hundreds of thousands of Americans throw themselves into debt for their insatiable wants? What do we do when the Earth cannot keep up with the natural resources depleted to meet consumer demands?

To explore these questions, the Spotlight staff has decided to investigate the ramifications of consumerism, the reasons for our desire to acquire goods, and how we may be able to rein in our indulgence before it is too late.

PAYING A HEAVY PRICE

Anything, and everything we want, has become increasingly accessible. Countless items line the store shelves at our disposal, and at the same time, these products fill up the space of our closets and cabinets. However, where the level of consumption rises to new extremes, it is no surprise that boundless consequences will follow.

With the advent of credit in the last 70 years, credit cards have significantly expanded people’s ability to buy goods and services by enabling them to borrow money with the promise to pay at a later time. This convenience, however, has led millions of Americans into debt, according to Christopher Bennett, social studies and economics teacher.

“There are tens of millions of Americans that carry debt on their credit card from month to month, because they’re constantly buying things that they can’t afford. People [buy] things now, [and pay] for it later, instead of the old school way of saving up,” Bennett said. “That’s why, per capita, our grandparents were way wealthier than we were because they saved up first and then bought stuff. Never paid interest. Everybody in our society pays interest on everything and that’s just wasted money. [It is a] 100% waste of money.”

According to Bennet, tangible consequences, such as debt, interest, and difficulty paying bills, will cause people to “sacrifice twhat [they] are gonna be able to do later in life.”

Mental health problems can be linked closely to debt. According to the Mental Health Foundation, debt can lead to various conditions such as anxiety, depression, and stress.

The impacts of overconsumption, however, can also extend past the individual person, breaching personal relationships. More than ever, material goods have increasingly become a symbol of status, dividing people based on what they have or do not have.

“We look at types of backpacks or water bottles or brands. Even when we talk about cell phones; I have an iPhone, there are people who have Androids and that can be a thing people group themselves into based on what product they think is better,” Mckenzee Johnson, junior, said.

With Stanley Cups dominating social trends, for example, these divisions have expanded to all walks of life. Earlier this year, according to CBS Austin, videos surfaced on TikTok of a nine-year-old bullied for owning an off-brand Stanley Cup. This pursuit of trends is tied to the desire to belong in social groups and avoid alienation, says The British Psychological Society.

Moreover, negative externalities arise on a broader level that, as the consumer, people often do not face directly. A consequence that manifests from consumerism is environmental degradation. According to FV Recycling, a waste and recycling service company, businesses produce approximately 25% of the world’s waste every year.

“We are using a lot of plastics, which are based on oil, and we’re using a lot of non renewable resources. We’re producing a lot of greenhouse gases that are in the atmosphere as we manufacture all that stuff,” Johnson said.

Matteo Gonzalez, junior, notes that it is not just businesses who are contributing to the problem; it is also the consumers themselves. According to a January Bear Facts Student Media survey of 246 students, 88.4% of LZHS students believe that the average person in Lake Zurich and the surrounding community overconsumes material goods.

“I think we have a lot of excess things. There’s products that are being overproduced that are ending up in landfills that are just piling up and [are] stuck there. It’s mostly plastic, molded plastic and things that aren’t biodegradable like clothes, for example. They can pile up with people that dispose of them incorrectly,” Gonzalez said.

Clothes, as Gonzalez explains, are items people commonly overconsume, thanks to the convenience of fast fashion. These kinds of clothing, Lucas McMahon, senior and EDvironment club president, says, are often of poor quality, making them unfit to be resold “because they wear out so quickly.” Other times, for styles that became popularized due to trends, “retail shops won’t take it anymore because it’s no longer a trending item.” As a result, these items find themselves disposed of, often lasting no more than ten wears, according to the Washington Post.

Similarly, technology is especially harmful in landfills. According to McMahon, a lot of people unnecessarily “replace their [technology] every two or three years.” Eventually, this leads to a “dramatic increase in e-waste.”

“[An iPad] has heavy metals, lead cadmium, mercury, and that’s to allow it to function,” McMahon said. “But the problem with it is, if it’s not properly disposed of, it can end up in your soils, and contaminate drinking water for populations. There’s crops grown, like corn [and] tomatoes, [and] when you eat the food from the land, you can actually be eating heavy metals.”

Discarded electronics from developed countries are often being imported where under pretense of still being usable. Per year, this waste totals up to 200,000 to 1.3 million tons of waste, according to United Nations University. Areas in Africa, such as Nigeria, the National Library of Medicine says, are major victims of such actions. Much of this technology is thrown in landfills and is subject to unsafe methods of extraction of valuable materials, posing threats to the environment and people nearby.

“There’s a lot of fine metals or rare earth minerals and what they do is they try to extract and sell [them] for money, but it’s creating such a big problem environmentally. [It also creates] health problems like chronic lung diseases, because they’re inhaling fumes from either burning it [or] trying to extract the metals,” McMahon said.

That is not to say consumerism lacks any gain; in fact, it is the opposite. Bennett makes the argument that consumerism “keeps the economy moving, [and] increases our GDP, which means we’re employing American workers, [and it] keeps businesses afloat.” Despite this, these benefits are offset due to poor consumer spending habits.

“Anytime you are spending more money in the economy, it is adding money that does not necessarily need to be there. Anytime you are consistently adding to spending, that is going to drive [up] inflation,” Bennett said.

Even so, the state of the economy is cyclical, and periods of high consumerism and materialism come and go. With the exception of the 2009 Great Recession and COVID-19, the American economy “has been very good for arguably 30 years,” according to Bennett.

“Right now, we’re definitely in that materialistic cycle. I think eventually that will go away as well,” Bennett said. “Then we’ll go back to focusing on more important things until we can build up to afford material goods again.”

EXPENSIVE ENTHUSIASM

Overconsumption has made its mark in almost every facet of our lives, ranging from the environment to our own emotional health. Despite having knowledge on the adverse effects of overconsumption, the rate at which we consume only continues to increase. It makes many wonder, such as Bennett, how we as a society have gotten to this point.

“At what point in time does [buying] become an obsession? That’s a good word for it: obsession. ‘I have to get the newest version just because I want to have the latest [thing].’ Why is that? What drives people to want that?” Bennett said.

The reasons as to why materialism and overconsumption maintain their overbearing presence in American society remain numerous. They can often be difficult to overcome, as they are implicit, and a result of social and psychological impulses.

In a materialistic society divided by “what you have and don’t have,” the compulsions for buying new items are often driven by the desire to “blend in,” according to Gonzalez. The concept of belonging is a universal human need, ingrained in our motivation as a species and our ancestral roots, according to Psychology Today, and is largely what drives us to follow trends.

“I’ve been super geared towards peer pressure in general. All these trends, why are we doing [them]? It’s because someone else is doing it and we’re pressured into participating,” McMahon said. “[…] People that they see [on] social media and follow were participating. All of a sudden they want to participate. They want to be part of this trend. They want to be popular, [try] to blend in, or be a part of something bigger. That is what people are geared towards, and that is why they do it.”

With social media’s fast-paced nature, trends have become just as fast-paced with microtrends: short-lived trends that gain high attention within a short period of time, and lose relevance just as fast. The microtrend cycle goes by much quicker than traditional trend cycles, prompting higher levels of consumption, as new items are constantly needed to “keep up,” according to the University of Melbourne. Often being associated with clothing and the fast fashion industry, microtrends are making a significant impact on consumer habits, affecting the quantity of clothes bought at a single time.

“A lot of bigger social media influencers tend to get sponsored by fast fashion retailers like Shein, or H&M, and other fast fashion [companies]. [These influencers] show off the clothes they got in the mail from a fast fashion retailer. All their followers look at it, and they want [that] particular item. They end up going to the site and buying whatever they want,” said McMahon.

Johnson adds that the digitalization of buying, online shopping, allows consumers to buy unnecessary items more conveniently, even for items outside the fast fashion realm.

“You can just buy [items] on Amazon [and] stuff shows up at your door. If you [had] to go out, and buy every book or movie, there would be a lot less impulse buys,” Johnson said.

Not only is the digitalization of our world impacting the convenience of shopping, it is also making advertisements inescapable. According to the University of South California, the average American in 2023 saw two million advertisements per year, an unprecedented number of approximately 5,000 advertisements a day.

“If I go back to when I was a teenager, unless I turned on the TV, I wouldn’t see advertisements, you know? Now, you guys are constantly bombarded with advertisements. […] [There is] advertising on Facebook, advertising on Twitter, advertising on television. Even if you’re watching Netflix, you’re getting advertising, unless you pay to get rid of it. You’re constantly thinking about those products,” Bennett said.

Today, it is possible for social media companies and advertisers to take users’ data and create detailed profiles to offer targeted advertisements, special deals, and more. Companies will also often cater advertisement campaigns to different groups of people, such as when companies create Pride Month campaigns, but do not thoroughly advocate for such causes outside of these campaigns, according to Johnson. Another example of such pandering is towards those who want to make sustainability efforts, known as “greenwashing.”

“[Companies] know that a consumer like you or me is looking for eco-friendly, sustainably sourced materials and clothing. What they’ll say is, ‘well, even though [our material] is not the best quality, we’re investing in recycling infrastructure, so, eventually, your textile can be made into a new one.’ But on the inside, they’re spending maybe two percent of their total profits on investing in this kind of stuff,” McMahon said.

Practices like these are at the center of investigations for misleading sustainability marketing, such as the Quartz exposé on H&M’s sustainability marketing. H&M used “scorecards” designed to inform consumers of the environmental impact of their purchases, using criteria such as how many fossil fuels and natural resources were used to create clothing pieces. Quartz’s investigation found that many of these scorecards were misleading, or downright false. Stories like these highlight the incompatibility between capitalist practices and sustainability, as “what’s better for the environment isn’t always good for bottom-line profits,” according to McMahon.

“Capitalism is all about earning profits. [Businesses’] incentives [are] to do whatever you can to earn as much profit as possible. Therefore, [they] are going to do [their] best to convince everybody ‘hey, you need to buy this product. You need to have the latest version of this product. You need to have things that you don’t need in general,’” said Bennett. “That’s what’s driving this whole thing: the fact that capitalism is chasing profits.”

“CHECKING OUT” SOLUTIONS

From head to toe, we are covered in items we chose to spend our money on. Our hair, clothes, and shoes are reflections of the advertisements and billboards that surrouds us. The ways in which consumer culture is perpetuated can often feel so normalized that our participation begins to feel implicit. How can we overcome overconsumption if we struggle to realize our role in it?

There seems to be a need for a national response, as overconsumption is shown to be potentially causing environmental harm. In fact, the Pew Research Center states two-thirds of Americans believe the government does not do enough to help the climate. McMahon, as one of those believers, thinks government regulations targeting the effects of consumption could potentially reduce our ecological footprint from materialism.

“The US government hasn’t passed any bill, specifically legislation regarding a minimum durability or lifespan standards for a variety of consumer products. [If they did, it would] help defend the consumers and ensure that a consumer doesn’t have to buy a product, such as a phone, with a short more than likely expected life of like five to ten years versus two years with functional obsolescence?” McMahon said.

Although government regulations could minimize overconsumption, according to McMahon, others argue that such directives are not viable in a capitalistic society, like the U.S.

“We’re so dependent on capitalism, as a society built on economic freedom. Consumerism [is] up for individual choice. You don’t necessarily want to limit individual choices. People want to buy things [and it’s their] right to [do so],” Bennett said. “That’s what economic freedom is. I have a right to waste my money if I want to.”

The idea of possessing the “right to waste” is often what lets consumers turn a blind eye to their problematic consumption and spending. Teenagers, specifically, are a group that are often unable to effectively manage and control how much money they spend, according to Business Insider. However, as people age, they are often forced to confront such habits and make amendments to how they spend their money.

“An example of this [is when] you go to college. The first thing you do is spend a couple thousand dollars to make sure you have all the cool stuff for your dorm. You want to have a big screen TV, so that all the kids can hang out in your room. You then want to have this big, huge stereo system, and you want to have a futon that everybody can sit on,” Bennett said. “You spend all this money, and suddenly you look at your credit card bill and then you are like, ‘Oh, I cannot afford any of this. I bought all this stuff, and I put it on a credit card, [but] I cannot afford it.’ Suddenly, that realization comes in that ‘man, I need to kind of cut back on spending all my money, and [I need to] actually pay off my bills.’”

Similar to Bennett, Johnson advocates for another individualistic solution for overconsumption: education. According to Pepperdine Graziadio Business School, educating yourself is one of the most powerful tools as research can lead to more educated decisions.

“[A potential solution is] to build awareness of the problem. I think a lot of people don’t realize [the impact of] how much they buy or the impacts of fast fashion or anything. There are a lot of people who will stop a bad ‘behavior’ when they see the impacts it has on other people,” Johnson said.

Researching and learning are good solutions for more than just fixing behaviors. For those seeking to support the cause of minimizing wasteful consumption, Gonzalez advises them to invest in sustainability as he believes it is the best way to minimize wasteful consumption, particularly in fast fashion. As our material use is crucial to our environmental and economic future, the United States Environmental Protection Agency says using materials with an emphasis on using less can help build our sustainability.

“Instead of buying trending items immediately, look at the quality of them, for example, so that [it] can last longer […] You don’t have to keep spending on lower quality items, [but] invest in a higher quality item instead,” Gonzalez said.

However, not all items marketed as high-quality and sustainable are what they seem. Therefore, McMahon advises consumers to educate themselves about corporate missions and spend their money towards honest efforts of sustainability.

“Look at the company; look at what they’re saying. Does it really like their green initiatives that they do? Is it really making an impact or not? [Then assess]: is this a company I’m still willing to buy [from]?” McMahon said. “There’s certain companies that you just have to buy from, but [see] if you can support locals in certain areas, because usually, local companies tend to have better recycling or community building initiatives.”

Many big fashion companies appear to have extensive green initiatives, like H&M, but do not fulfill said goals. In 2023, the company was accused of greenwashing — when corporations falsely appear as eco-friendly — because they overstated the sustainability of their clothing, according to Forbes. Such practices exemplify the importance of researching where consumers spend their money, as those with good intent could actually be supporting harmful actions.

With such degradation to our environment, overconsumption is likely a difficult and persistent issue to tackle. However, the simple efforts of cutting down our expenses and investing in sustainable items start with one person at a time and can only lead to hope for a reduction in the consequences of our spending habits.

“I don’t think [overconsumption] will get much better because of social media, influencers, and our culture so far,” Gonzalez said. “I think it can be shifted towards a positive aspect in the sense of limiting how much we spend or how [many eco-friendly options] companies are offering[…] With new generations, [people] might be more educated, so they will be less likely to overconsume as previous generations have.”