EMPHASIS ON PRESTIGE

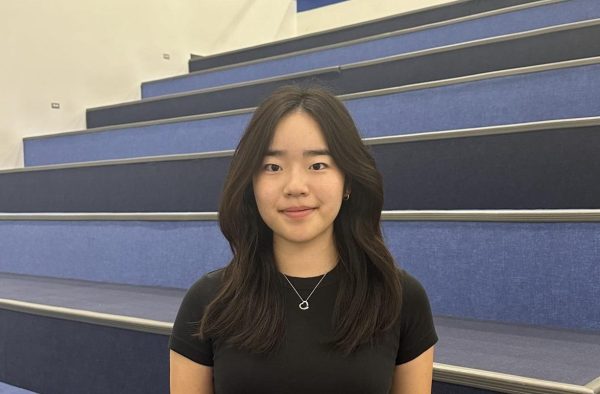

America’s college system has long been characterized by its reputable schools where admission to one is often considered a ticket to a life of guaranteed success. With college acceptance rates decreasing each year, according to the National Association for College Admissions, some people like Caroline Sun, LZHS alumna and Cornell University student, feel heightened external pressure to achieve admission.

“In my eyes, because [of] the way [my parents] raised me, college was kind of like the ‘end all be all, you know? It was the beginning of everything: how you got your [career] started, how you met the people you needed to know, and how you got the skills to succeed in the job market,” Sun said.

Carl Krause, post-secondary counselor, says he’s noticed this notion many students and families have regarding the prestige of a college marking the trajectory of a student’s future. Yet, by referencing a study that disproved the myth of Ivy League graduates having a monopoly on high salaries, Krause disagrees with such assumptions. Conducted by economists at Princeton and Mathematica Policy Research, the researchers’ longitudinal study concluded that Ivy League rejects with similar SAT scores enjoyed similar average salaries to Ivy League graduates.

“If you’re academically strong, that [won’t] change no matter where you go to college. If you’re a hard worker, why would you be better at one school than another? You’re the same kid. You’re going to do just the same things at a different place. Why wouldn’t you be just as successful in 10 years?” Krause said. “It really has nothing to do with your schooling. It has [everything] to do with the student. It’s [all] about you.”

All of this isn’t to say, however, that there is no merit in aiming high for top schools. Attending top schools can provide influential networks, state-of-the-art facilities, and professors at the top of their field, according to Forbes Magazine.

Miles Adler, senior, says that going to a prestigious college may allow students to get out of the Lake Zurich environment, see “a completely different part of life,” and challenge students in a ways they have not been before.

Similarly, Jane Doe, whose name has been anonymized for privacy reasons, says that if a top college has one of the best programs for one’s major, it should be a heavy consideration in college decisions. Despite the benefits, Jane expresses animosity over the sense of “elitism” that follows such schools. In her experience, those without plans to attend reputable four-year colleges have to deal with judgment from others. For example, Jane says she feels many “associate community college with failure.”

Planning on becoming a radiologist, Jane feels the best way for her to gain experience and a “feel for the field” is to get an associates degree from Harper College as a radiological technician. From there, she plans on transferring to a college with a diagnostic imaging major, and then apply to medical school. Still, she encounters disappointment and concern from adults in her life that she “looks up to,” and even friends.

“It makes me feel like they can’t overlook their beliefs to listen to me, and how right this feels. I already have a plan and it makes me feel like they don’t listen to that part because they can’t get over the part of where I’m going,” Jane said.

To get past preconceived notions over non-prestigious schools, Jane says people need to reframe how they go about discussing college.

“We just need less of a stigma. If there’s not as much of a stigma then it would be less about the prestige. I think [there] needs to be less emphasis on ‘we’re going to this college,’ or like ‘they got in there, but they didn’t get in there.’ Discussions should be more about ‘what are you excited about for your future? What do you want to do with the rest of your life?’” Jane said.

Furthermore, Jane says that “name brands” should not be held in such high regard. Instead, atmosphere, social life, teachers, class sizes, and other crucial factors, should be primary concerns, as different students have different needs.

Krause agrees, calling himself a more “fit type of advisor.” He hopes that students start to focus on this “fit” aspect, and trust that success will naturally follow them if the environment they are in is optimal for themselves.

“We don’t trust ourselves enough. You [are] the exact same student no matter where you go […], regardless of what a college says to or about you. [When you get rejected,] it’s not about you,;it’s about what they need at their school,” Krause said. “[…] I think once we start figuring that out, believing in ourselves a little bit more, stop listening to the hype, and reading the rankings, [we realize] none of that matters. […] You should be able to do well anywhere if you’re a good student. We need to stop worrying about name brands, and just trust ourselves.”

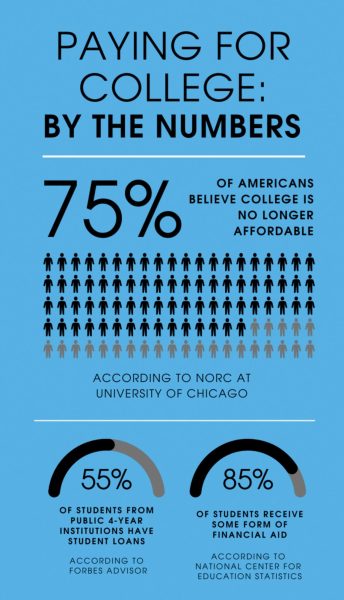

FINANCIAL DISPARITY

Between 1980 and 2020, the average price of tuition, fees, and room and board for an undergraduate degree increased 169% in the U.S., according to a report from the Georgetown University Center on Education and the Workforce. With the average private college costing around $48,965 per year and the average public college costing $21,035 per year, it should come as no surprise that paying for college has become a challenge for most students and their families.

While the struggle to pay for college transcends socioeconomic classes, it is particularly difficult for those of low-income families, such as Adler.

“Before I was assured that FAFSA could pay for my needs, there was a good chance that I would only be able to go to community college because if colleges didn’t want to meet our financial aid, I wouldn’t be able to go. I can’t take out $70,000 loans every year. Neither can my parents. We’re not gonna get those loans because we’re dirt poor and the bank says we can’t pay them back. Even if we did get loans, we can’t pay them,” Adler said.

The ability to afford college is a factor that causes stress in Adler’s life, as he finds it essential to “do something with [his] life and achieve the goals that [he’s] dreamed of.”

Adler is not alone in this struggle. Krause says that “a lot of [LZHS] students would be surprised with how [many] of their classmates are low-income.” As the post-secondary counselor, Krause has tough conversations “every year” with low-income students trying to pay for college. Often, sacrifices have to be made.

“[You could] just be doing [college] online instead of at a four year university. Some students are worried about the college experience, but is [that] really the best for them and their family? That’s really what it comes down to: what are you willing to do?” Krause said.

However, some students, like Adler, cannot afford to make such sacrifices. Adler finds it “unfair” that he might have to reduce his ambitions because of his families’ income.

“I deserve to have the same opportunity as someone whose parents make six figures, but I don’t. It’s genuinely not fair. It’d be more fair if I had gotten myself into this financial situation, but I was born into it,” Adler said. “If I stay in this town, if I go to community college here, I will end up in the same cycle. Because of the position I was born into, I have to go through more barriers to get a worthwhile education that will get me out of the cycle that my parents have started.”

One barrier Adler draws attention to is the saturation of need-aware colleges, such as Boston University or Tufts University, that take students’ ability to pay college tuition into consideration. This means that, hypothetically, if a school is trying to decide between two students, they may choose the one who requires less or no financial aid because it is cheaper for them, even if the college advertises as meeting full financial need.

“They need to pay for their buildings. They need to pay their employees. They need to pay for your ribbon bar. It’s still a business. […] They can’t give everyone a discount, a percentage break, or a scholarship. It just doesn’t happen,” Krause said.

As a result, multiple initiatives have been put into place to make attending college accessible for low-income individuals. When asked if such measures put into place were enough, Krause says that they are “never sufficient.”

Adler agrees and says that a “lot of stuff looks perfect on paper and can be really good opportunities,” but there can always be caveats. Before his senior year, Adler considered using the well-known QuestBridge’s National College Match: a college scholarship application process that helps academically strong low-income students gain admission and a full four-year scholarship to 40 of the nation’s most selective colleges. However, only a fraction of applications go on to receive admission and the scholarship. Although he believes it is a “great opportunity,” it has its cons.

“Most of the schools I want to go to are not partner schools. It’s also much more selective than the regular process. You waste so much time during the application process [for QuestBridge]. Say I applied to their partner schools; by the time that I get my rejections, I would only have two weeks left of the regular decision deadline to reapply to the schools that I actually wanted to because of a rule that doesn’t let me apply to other schools before [December 3],” Adler said.

Further, the QuestBridge process is only for academically strong students, as it requires primarily A’s in rigorous courses, an SAT score of over 1310 or an ACT score above 28, and a class rank within the top 5-10%. This is not viable for many low-income students, as “historically lower income areas or schools may not have the same things educationally,” according to Krause, differing greatly from LZHS’s environment.

“You guys walk into Lake Zurich High School thinking ‘I’m going to college.’ We send over 90% of our kids to college. That’s a crazy high number. There are some schools that don’t even graduate 90% of their kids. It’s all about the mindset; it’s all about exposure,” Krause said.

Unlike LZHS, many schools do not have the resources for post-secondary counselors, and as a result, students do not develop the “confidence and drive” to navigate the college admissions process. To tackle this issue, Krause says to look at new college application models set up by companies like Niche and Concourse.

“You fill out a profile, put it out there and colleges give you admission just [through] that. You don’t have to apply. […] Colleges reach out to you and say ‘hey, you’re a perfect fit; if you make it to our school, we’ll give you a $10,000 scholarship to do that.’ […] I think it is really going to change how admissions looks,” Krause said. “It’s going to be great for students that don’t have the exposure.”

REASSESSING STANDARDIZED TESTING

With the strenuous hours of filling out college applications comes the obstacle of standardized testing. In the recent years following COVID, many colleges have remained test optional, some even becoming test-blind: this adjustment being the first since decades of years of requiring SAT or ACT scores. Since this change, many have responded in differing ways.

Krause says this development is “one of the best changes we’ve had in 50 years of college applications.” Although going test-optional may increase students’ confidence, it does not account for the impacts testing has on students. Since schools still require students to take standardized tests, there is still a lot of stress regarding the testing experience. Adler even goes as far to say he “despises standardized tests” because of current standards.

“The bar has been set so high with scores because of SAT [preparation.] [For example], a 1230 [score] is not even bad. In this day and age, it is seen as horrible because everyone is aiming to get like 1400s [or 1500s] because the bar has been raised so high,” Adler said.

Echoing Adler’s statements, Krause says that he finds it difficult telling students whether or not they should submit their test scores because the bar is set so high, hurting students’ mental health.

“I have many conversations with kids [who ask if they] should send [their] score to colleges. This is hard to answer because even if you’re in [the] 50th percentile of admitted students, you always feel insignificant, like it’s not enough. I hate having that conversation because it’s such an unnecessary evil part of the application process,” Krause said.

Having already gone through the testing and college application process, Sun expresses her opinions on the SAT and the ACT.

“I don’t think [standardized testing] is necessary. When you have a job, they don’t give you tests [nor do] you have to memorize [information] for the test. That’s not how the real world works,” Sun said. “At the end of the day, it’s not about how well you can [win] the system, it’s about knowing things you also have to know.”

However, it is the unfortunate reality that standardized testing remains about “winning the system.” This game is not easy however, and many students, including Adler, have unbeatable obstacles that make them incapable of succeeding in such a controlled environment.

“I can’t focus because I can’t sit in a room taking a test for three hours. Second of all, I don’t think that standardized testing is fair for people unless you are good at math, for example. The math standardized testing portion sucks, not just for me personally, because you don’t usually remember stuff that you learned like freshman year for a month. Yet three years later, you were supposed to sit and try to answer 30 questions on [those] topics,” Adler said.

Alongside his inability to focus, Adler says he is unable to handle the costs to “win the system,” due to being of low-income.

“I can’t afford an SAT tutor. Also, I don’t understand why people would want that. Why are you spending thousands of dollars for one test?” Adler said. “Yes, it’ll help if you’re lacking in other areas. If you suck at standardized testing, but your grades for the last three years have been amazing, you have really good AP test scores [or] maybe you do extracurriculars, you do not need to spend insane amounts of money for a [test].”

Nonetheless, being test optional or test blind has not translated to all parts of the college application process. Many top-ranked colleges still require SAT and ACT scores and even more require them when applying for scholarships. Yet, despite others’ disapproval of this fact, Jane says that the continued prominence of test scores may not necessarily be a harmful thing.

“You are not your test score. [But] some people can show [a lot] with a test score and some people can’t,” Jane said. “[Still,] I don’t think standardized tests should go away because [some] people can do well on standardized tests [and] you should give them that [chance].”

Contrary to Jane’s perspective however, the extraneous amount of effort directed towards one score is deemed unnecessary by many others. Coming from a professional perspective, Krause says that the test score is truly insignificant towards the holistic view of a student because it does not truly measure intelligence.

“The test score is such a small piece of what the kid actually knows and can do because [the student is] only measured on one test for three hours. Your grade point average–what you do every day for three or four years–is a better indicator of what kind of college student you’re going to be than the test scores,” Krause said. “[…Tests] truly have nothing to do with success.”

A WORK OVERLOAD

Each year, universities across the country receive thousands of applications, with top schools receiving upwards of 80,000, according to U.S. News and World Report. However, behind every senior’s application is countless hours of drafting and even years of overworking themselves for the sake of college admissions season.

“[Colleges] want students who have put in the effort throughout the years, who have shown ambition, who have worked to prove themselves and who want to go to college and beyond to better the world,” Sun said.

Though this demanding process has become the norm, some people, like Sun, find that the consequent workload and requirements are exhausting. She says her ambitious personality and desire to pursue her goals made her “willing to put in the work and do what it took to get into a good college.” Sun applying to 13 universities resulted in four months of researching colleges and writing over 30 college essays.

“College applications are draining. It forces you to look at yourself in a way you’ve never looked at before. You would look at every aspect of who you are, how you became the way you are, know what you’ve done, and how you put your best foot forward,” Sun said.

These overwhelming feelings are universal, as 74% of college applicants reported “Very High” or “High” stress levels about their applications, according to The Princeton Review 2022 College Hopes & Worries Survey. Unfortunately, excessive stress can have negative ramifications, the National Library of Medicine says, “including ill health, anxiety, depression, and poor academic performance.”

Krause acknowledges that the admissions process is stressful, especially due to a “fear that the process is really hard.” Reading through dozens of college applications, he recognizes the wide range of skills that students have and accomplishments cultivated due to such anxiety. Despite their source, these achievements remain impressive, as he says compared to his own high school years, not many of his friends were doing research, internships, or year round activities like students today.

“Kids are way more complex now. I think it’s great for [our] country because if we were all the same, [it would be] a boring place,” Krause said. “You guys give me some hope that we’re going to keep moving forward and hopefully […] try and fix some things, be it environmentally or socially. One friend of mine went out of state for school. Now, half of you go out of state for schools. Kids are braver and more ready to do things. I just am amazed when I see what kids are capable of.”

On the other hand, Sun, believes the admissions process has “become more of a competition [or] pageant” rather than a reflection of students’ true passions and potentials.

“People will literally start companies or nonprofits or clubs because it’s something colleges care about. It starts to feel more and more performative,” Sun said. “I think in that way, it’s really messed up. You are making high school students cater to college admissions, and cater their whole lives to something they might not even care about, but have to [do] just to get into college.”

While this may be true for some students, others, like Adler, have decided that they do not find it necessary to cater to college expectations at all. For him, finding the time to participate in a lot of extracurriculars is difficult, due to his work and family obligations; it is not worth “stretching [himself] really thin” just to get into college.

“I put a boundary on how I spend my time. [Hypothetically,] I am not going to get up at six in the morning for school and go to bed at three a.m. [for clubs], because on top of work, I have to do homework because I’m balancing three AP classes and two honors classes my senior year. I don’t need to be doing all of that just to prove to a college that I should be accepted. What should matter is that I’m doing something with my life, which I am,” Adler said.

Krause agrees with Adler’s sentiment and adds on his “biggest message,” which is the importance of being able to trust in oneself and where they will end up in their future.

“You may not get into this selective school. Most people don’t, who cares?” Krause said. “But you’re gonna get some of them, they’re gonna love you, you’re gonna love it there; you’re gonna find your people, and it’s gonna work out.”

Disclaimer: changes were made post-publication to this article to protect an individual’s privacy.