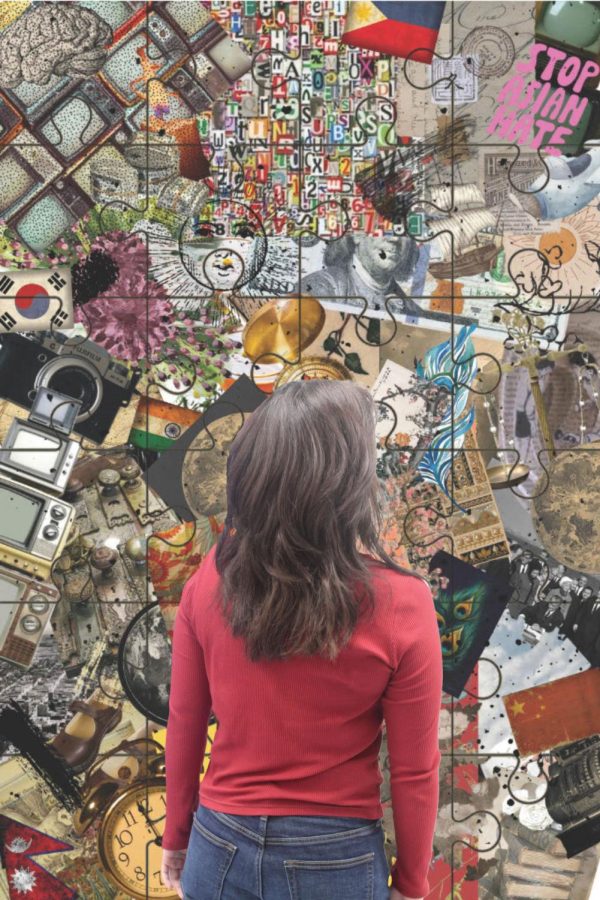

Collecting the pieces of the Asian American experience

With the signing of the 1965 Immigration and Nationality Act, the racial landscape of the U.S. was permanently altered. In what was expected to mostly benefit Eastern European countries, the decades following the 1965 law showed a boom of Asian immigration to the U.S. By the 1980s, Asian immigrants accounted for the majority of the immigration population. With this newfound population, the Asian American identity was constantly being molded and configured. Even to this day, it is ever-changing.

However, for as long as it has existed, the idea of conceptualizing a shared Asian American identity has shown itself to be challenging. How can one term encapsulate the decades’ worth of experiences of people with very different ties to dozens of countries?

The spotlight staff believes that there is a unique challenge in navigating our own identity in a nation where the label “Asian” brings expectations about our origin, behavior, and physical self. For this spotlight issue, we have brought together students from the LZHS community that provide an intersectional representation of the Asian American community. The purpose of this Spotlight issue is to bring an awareness of the multifaceted nature of Asian American identity and bring together different pieces of the “collage” that is the Asian American experience. Our goal is not to collectivize Asian American individuals and communities, or reduce them to a monolith. Rather, we are seeking to celebrate the uniqueness of every piece of the “puzzle.”

RACISM

Mentally, racism can affect people and students alike by causing feelings of insecurity, the development of internalized racism, and a decrease in self-worth. Asian-Americans are the least likely to seek out help than any other racial group due to cultural bias against receiving treatment, according to the American Psychological Association.

Lia Carroll, Taiwanese-American sophomore, says she witnesses racial ignorance in the microaggressions of those around her. One of those slights is that teachers frequently call her by the names of other Asian American students.

“It makes me upset [because] we’re different people and don’t really look alike,” Carroll said. “It’s that saying like, ‘oh, China’s a whole country of cousins,’ and it really messes me up that [they] don’t even see me as an individual.”

Carroll has felt the brunt of people’s racial insensitivity was in middle school when one of her close friends would make fun of her eyes. At the height of the ‘Stop Asian Hate’ movement, a classmate called her and a fellow Asian American peer “coronavirus.”

Stereotypical remarks have substantial effects on those who receive them that permeate for years.

“As someone who is not white, growing up I realized just how differently people perceive me than what is ‘normal,’” Roxanne Liang, Chinese-American senior, said. “It made me have really big self esteem issues.”

Partially, Liang says this feeling of alienation stemmed from media portrayals she saw online that would use “shock-value or offensive humor” to depict Asian Americans and sometimes come from Asian Americans themselves: something she believes “comes from systemic racism.” Liang also felt discomfort with her identity was ingrained by the curriculum of her history classes.

“When they discuss the small bit of Chinese history that they even include, there’s just always this feeling of ‘otherness,’” Liang said. “Especially with things like the Red Scare– I know the detrimental effects of attempts at communism in history, but still there’s a feeling of stigma against Chinese people because of it […]. They talk about Chinese people like they’re something ‘other.’”

In broader context, many students feel racially fueled discrimination has seen an increase in recent years, and the coverage of anti-Asian incidents in the news has caused various concerns for Asian American families.

“It’s always really sad,”Angelina Chai, Chinese-Lao American senior, said. “It could be someone’s grandma or grandpa, some innocent family member, and they’re being harassed.”

Julie Lee, Korean-American senior, feels that in part this rise in discrimination can be attributed to the spread of COVID and its additional consequences in a spread of xenophobia towards Asian Americans.

“[Racism has] gotten worse. A lot of people are starting to resent Asians in general,” Lee said. “I feel like generalizing this to all Asians is just so unfair because it’s not something that we want and it’s not something we could really control.”

LANGUAGE BARRIERS

Language plays an important and personal role in people’s lives. Its role in connecting individuals and communities is often an integral part of the Asian American experience.

According to a Bear Facts Survey of 52 Asian-American student respondents, 38.5% said that they could speak and understand their native tongue. Likhith Donapati, South-Indian American sophomore, says being bilingual helped foster a sense of belonging with those who speak the same language as him. Since English is not his first language, Donapati had to work to improve his proficiency in English.

“When I was in kindergarten, I did not know any English at all. That whole year it was me pushing myself to learn so I [could] speak English. Some of my friends in that class spoke the same language with me so they would help me become better at English,” Donapati said.

Bilingualism also presents advantages, as it allows Asian Americans to maintain familial connections. For example, Jon Han, Chinese-American senior, says speaking Mandarin has helped him strengthen his relationship with both his immediate and extended family.

“My parents are able to speak English, although it is a little bit broken. Ever since I was little, I’ve been able to help translate [for my parents],” Han said. “I think it has strengthened my relationship with my extended family [in China] because they speak little English. I’m able to call them, understand them, and talk with them.”

However, unlike Han and Lee, Carroll is unable to speak her native language. Due to this, she has experienced difficulties arising from language barriers between her and her relatives, and says she has developed a sense of feeling like an “imposter” within her own family.

“I’m definitely the least favorite of my grandma’s grandkids because I can’t speak Mandarin. We went to Taiwan a few years ago. I couldn’t talk to my [great] grandmother because she doesn’t know any English. I don’t even know who she is, [or] my great uncles and aunts,” Carroll said. “I was always worried they were judging me because I couldn’t speak the language like, ‘Oh, this provisional American girl who’s only one generation away from us [can’t speak Mandarin].”

However, the burden of language barriers is a two way street. The U.S. Department of Health and Human Services Office of Minority Health states that 30.9% of Asian Americans are not fluent in English. Lee has seen the negative effects of this barrier on her mother. When she was younger, Lee and her mother went to a shoe store. Her mother put down the money for the shoes and when “she looked up, the money was gone.” The cashier asked her to pay the rest of the money.

“I saw her put it down, but as a child, I couldn’t speak up about it because I wasn’t sure. [The cashier] said she didn’t put it down and they [argued]with her,” Lee said. “My mom couldn’t express verbally what she had to say, because of the communication barrier. She asked to roll the security cameras, [but] they said that there were none and we couldn’t do anything about it. We just left the shop [without our] money and with no shoes.”

MODEL MINORITY MYTH

The University of Washington’s Stereotypes, Identity, and Belonging Lab, interprets the term ‘model minority’ as a characterization of minorities who have “ostensibly achieved a high level of success in contemporary US society […] used most often to describe Asian Americans, a group seen as having attained educational and financial success relative to other immigrant groups.”

Stereotypes that attribute higher levels of academic proficiency to Asian-Americans are “very prevalent” according to Lee, who says pressures to uphold standards based on being Asian pervade multiple areas of her life.

“Sometimes it’s a joke, ‘oh, she’s smart because she’s Asian,’ I hear that a lot around [school],” Lee said. “Also going to a [Korean] church every single Sunday you hear about other people’s successes and who’s smart and then that kind of becomes a big topic.”

Similarly, Aarushi Bhagath, Indian American sophomore, notices “people associate certain ethnicities with certain stereotypes.” When discussing schoolwork, Bhagath says she is often met with responses equating her achievements to being Indian, and she has been frequently asked whether she wants to go into career fields stereotypically attributed to being Indian, such as IT.

On a surface level, sentiments of innate success in school or in the workplace may come off as complementary, but Donapati has felt they can downplay individual effort.

“Sometimes it’s like, ‘you’re smart because you’re Asian, not because you try hard,’” Donapati said. “The fact that you’re Asian in this big of a school where over 70% is [white] can really affect you. You’re trying to achieve what you want and what your parents want for you, but people are undermining your abilities by telling you, ‘the only reason you’re good is because you’re Asian.’ […] It can really hurt your mental health and how you perceive others.”

Adversely, some like Han feel this perception of Asian-Americans can be advantageous, and even motivational, by setting high expectations to live up to.

“I think that stereotypes that fall into the model minority myth can have harmful repercussions on students that want to achieve [what] may be outside of a reasonable reach,” Han said. “However, for me, I don’t think it has had any repercussions. It has actually helped me because it has enabled me to work harder to achieve better both academically and athletically, and to excel in my extracurriculars.”

While Han says that these standards tend to foster competition within Asian American communities, he believes they also have the potential to lead Asian American students to “encourage and lift each other up.”

But this idea of “beneficial” stereotypes is possibly at the root of the various pitfalls and ramifications of the ‘model minority’ image. Expressing that its “not just about stereotypes,” Liang finds that the ‘model minority myth’ definitely does harm,” due to a neglect to acknowledge the nuance behind what the concept promotes.

This extension of thought begs the question of whether or not the stereotypes even hold true. In 2018, a report by Pew Research Center reflected that Asian Americans have the greatest wealth gap of any ethnic group. Liang says she became cognizant of this polarity seeing how the ‘model minority myth’ is weaponized against other marginalized communities.

“The thing with poor communities in America is […] non-white people have just been systematically oppressed from the start; they’re not given opportunities, and a lot of Asian immigrants are only able to come here because they were originally privileged in their own country,” Liang said. “A lot of people are just not aware of that [disparity] so all they perceive it as is, ‘well Asians, they’re working hard, and that’s why they’re successful.’ Then with other minorities, [people assume] ‘they must just not be working hard’ and that it’s not a thing of privilege or oppression.’”

The privileges and hierarchies that come to fruition from the “model minority myth” are something that Liang says can cause “people [to] collectivize” with others who fit into the ‘model minority’ role in a survivalist attempt to assimilate. Han says that he has a desire to fit into the “common stereotypes that East Asians face” of performing well in academics.

“Since the stereotype is such an especially prominent one, I feel a need to fulfill it,” Han said. “I think that other East Asians also feel that it is necessary for them to fulfill it too.”

GENERATIONAL GAP

There is no denying that for many immigrants, the U.S. is a land of opportunity. This is no different for many Asian immigrants choosing to start new lives in the U.S., hoping to escape economic hardship, political tyranny, and poor education.

“In China, [the part from] where my parents are from, many don’t even have the chance or opportunity to accumulate capital or start any businesses. It’s very difficult for any person who [wants to] pursue any of their own goals or ambitions. I think that that’s why you see so many East Asians especially [immigrate] to countries like the United States,” Han said.

The cultures of the east and west differ vastly in terms of values and attitudes, according to an article in the Journal of Youth and Adolescence.

“A typical scenario finds immigrant parents adhering to their traditional cultural beliefs while their children endorse dominant Western values, resulting in a clash. This clash is likely to be more serious among families from non-Western cultures, such as Vietnamese and Cambodian families, who share few commonalities with mainstream U.S. culture” according to another article published in the Journal of Youth and Adolescence.

As Chai describes, often it is expected that the family’s needs as a whole come before an individual’s needs to help everyone.

“A lot of times you’re supposed to do something that benefits the future of your family as a whole. Just going off on your own and doing something individually. You’re trying to help everyone as a family, especially like paying back your parents,” Chai said.

Chai says that when she goes against certain collectivist values of respect to parents, such as giving an opinion too strongly, her parents become worried that she’s “becoming too American and straying from [her] native culture.”

However, the pressure does not go one way. Children can implement their own values onto elders. An example of this is with Lee and her grandmother, who was born and raised in Korea.

“[My grandmother] was born in Korea and lived there for basically the majority of her life. I think that really carried on over here and I started seeing that a little bit,” said Lee. “Especially when it comes to roles, like doing the dishes — the guys do nothing. I definitely do see my grandma, but I’ve been teaching her, [and] she’s gotten a lot better at it for sure.”

For many Asian-American students, such as Lee, the solution to these generational clashes is having a community of other children of Asian immigrants to talk and relate to, such as those at her Korean church.

“I think it gives me someone to relate to, because there are some things that I can’t really talk about, with people who aren’t familiar with Asian culture or especially when I talk about my parents’ behavior, cultural events, holidays, and stuff like that,” Lee said. “I can definitely talk to church people more than I can with my friends at school.”

Coming back for her last year on Bear Facts, Gurneer will be Spotlight Editor for the second year in a row. Outside of Bear Facts, she participates in...

This is Jane’s third year on staff and second year as Digital Editor-in-Chief of Bear Facts. Jane is involved in orchestra, Tri-M, NHS, Sinfonietta,...

Going into their third year of being on the Bear Facts Staff, Kara hopes to take on Lois Lane-type capers as a senior. If you were to spot them outside...

As a senior, this is Grace’s third year on the Bear Facts staff, acting as Spotlight Editor and secretary. In her free time, she enjoys running (sometimes),...