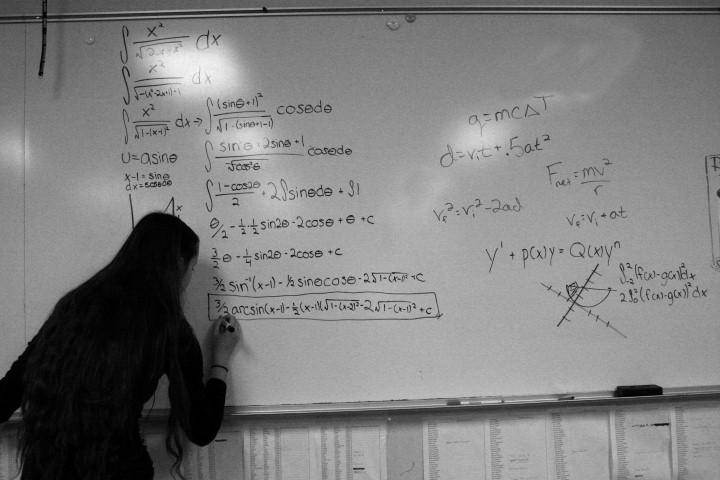

There are two features of the AP Physics class at LZHS that are more easily recognizable than the rest. The first is that the material is not easy. The second is the total absence of females in the classroom.

There are currently zero girls enrolled in the double period AP Physics class of 20 students. But this unbalanced gender distribution is not confined to one class; it can be seen in other math and science classes such as AP Calculus BC, where the ratio is seven girls to 17 boys.

In LZHS AP math and science classes, there are 29 more boys than girls in total. When excluding Biology and Environmental Science, which are less mathematically based, that number increased dramatically to 61, where boys make up about 62 percent of the total students in those math and science classes.

“I think boys tend to be more interested in math and science, while girls are in more art and English classes that are more creative and less math-based,” Katherine Conlon, senior in AP Calculus BC, said. “It seems like it’s always been like that, even in elementary and middle school, where most of the other people in the advanced math classes were boys.”

Conlon, who plans to major in engineering in college next year, is aware that she may be in classes with more boys than girls throughout her college experience, much like her AP Calculus BC class in high school.

“I know there are significantly more boys than girls in fields like engineering. As a girl who wants to go into engineering, I feel outnumbered, but that’s not necessarily a bad thing because I stand out more and I can get different scholarships to college,” Conlon said.

Only one in seven engineers are female and women hold fewer than 25 percent of all jobs in science, technology, engineering, and math (STEM), according to a 2011 report by the U.S. Department of Commerce. This indicates that girls’ lack of interest in math and science extends past the high school level. Causes are wide-ranging, the report said.

“There are many possible factors contributing to the discrepancy of women and men in STEM jobs, including: a lack of female role models, gender stereotyping, and less family-friendly flexibility in the STEM fields. Regardless of the causes, the findings of this report provide evidence of a need to encourage and support women in STEM,” the Department of Commerce said in the report.

The Department of Commerce’s view on the variety of causes of the gender gap in STEM fields matches that of Eric Hamilton, assistant principal of curriculum and instruction.

“My job is to try to see the cause of the discrepancy. Are students not taking AP Computer Science because they’re taking AP Calculus instead? When you’re looking at Physics and looking at Calculus, Physics is kind of a Calculus-oriented class. So why aren’t the girls in Calculus taking Physics? Is it a scheduling issue, because Calc is one period and Physics is two periods? I can’t really give any definitive answers, I can only ask questions,” Hamilton said. “I think what we have to first ask ourselves is what’s causing the discrepancy. We have to look at the numbers and see the extent of the problem, then go from there.”

Some may explain the different gender distributions in math and science classes with a simple stereotype that boys are smarter than girls in STEM fields. However, test scores shows that this is not the case. Although the enrollment of girls in such classes is lower, the scores of the girls who do take the classes are approximately on par with those of their male classmates. In 2012, math and science AP scores of LZHS girls were an average of just .161 points lower than the math and science AP scores of LZHS boys.

Hamilton believes that schools can make a difference in the number of girls in math and science classes if an effort is made to research the topic and find solutions. LZHS has taken some steps to do so already, he said, and it could have effects beyond just high school.

“We’ve talked to Industrial Tech teachers about how to get more girls into engineering. Females can see some things that males can’t, especially creatively. More girls in engineering would help teamwork, would create a more diverse environment, so that’s something we’re trying to do,” Hamilton said.

The divide between girls and boys in different subjects may start at a young age, Hamilton believes, and if the process begins early enough, he is optimistic that progress can be made.

“I hope my daughters get the opportunity [to explore math and science],” Hamilton said. “It comes down to what messages we give kids; in particular, young girls.”