Why so specific?

Students question whether or curriculum is applicable to the real world

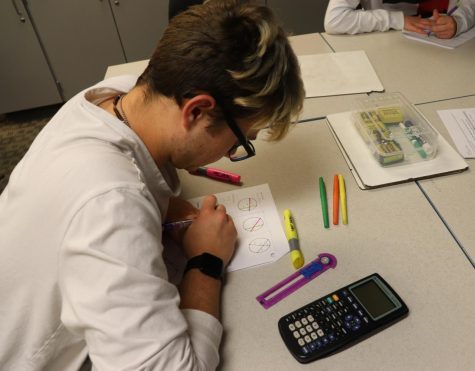

Photo by Photo by Ellie Melvin

Margaret Koy, math teacher`s students practice new problems in class. When students ask why they learn something, “I don`t want to be saying, `Well, if you do this job, then you`re going to do this,` and then they inevitably say, `That`s not what I want to do, so why does it matter?`” Koy said.

Students learn everything from which trophic levels an eagle feeds on to how to calculate the inscribed angles of a circle, sometimes in a day’s work. These kinds of lessons are not necessarily applicable to all students’ futures, so why are such specific skills taught? Alaya Arslan, sophomore, says she hears this question all the time.

“[I hear it] especially math and even English, which in my opinion, I find English to be one of the most important, if not the most important subject.” Arslan said. “[I’ll hear,] ‘When are we ever going to need this in our life or career?’ I heard this example, ‘When am I ever going to find X when I’m at the grocery store?’”

When remarks such as those are thrown away a classroom, Sunny Lindgren, sophomore, says she can understand where students are coming from since she has had her own similar frustrations before.

“It’s definitely a lot harder to learn when you’re fixed against something from the get-go,” Lindgren said. “When you’re automatically thinking, ‘I hate this. This is stupid. I’m never gonna use this,’ It makes it far more difficult for you to learn that thing, so I guess you just need to be open-minded with what you’re learning.”

Arslan, however, has a different reaction to hearing such questions in class.

“I kind of roll my eyes because [some students] don’t understand how privileged they are,” Arslan said. “Everyone in my family had to fight for their education basically, and my mom would constantly remind me of these struggles. It’s definitely shaped my viewpoint to say the least. So I do find it annoying, but I can understand it because they likely don’t have parents who have lived in the Soviet Union, [and] didn’t have to undergo such struggles to obtain their education.”

Students are not the only ones who hear these questions. In fact, teachers are sometimes in a position where they are expected to address the frustrations. Margaret Koy, math teacher, has been in these situations, and says the questions can be difficult to answer.

“The thing I see [behind those questions] is the fear that, “Well, I’m not going to be able to do this”, and then [some students] don’t even try. And they just throw their hands up and walk away from it. And those are the most frustrating cases because it’s like, ‘No. You don’t understand the power that you actually have.’ That’s probably the most frustrating thing as a teacher. Because I cannot force them to do that. That’s the realization everybody comes to on their own.”

In an attempt to answer students, Koy has sometimes told them that they learn the curriculum because it is built on later in their education. But there’s more to the story.

Margaret Koy, math teacher`s student follows class notes on a new math concept. “There`s so much value in pushing yourself until you realize you can do it,” Koy said. “It`s a tremendous life skill. Absolutely tremendous.”

“What [we teachers] do more often, or is [more] valuable, is teach you how to think. Teach you how to analyze,” Koy said. “And those are some real skills: the perseverance, the discipline, the critical thinking, and learning how to deal with mistakes. I mean, that is the whole journey that everybody has to go through while they’re maturing.”

Though learning how to push yourself to success is an “absolutely tremendous life skill,” Koy says, Lindgren and Arslan believe there could be some more focus on practical lessons students may need for their immediate future.

“It would be nice if there was some sort of class that taught us how to apply for jobs, what the college admissions process [is], what they’re really looking for, and things like that. I guess FAME is that, [but] you learn that freshman year and then you forget about it by sophomore year,” Lindgren said.

To satisfy students frustrations, Arslan proposes focused career-related lessons.

“I feel like nowadays some new career paths could definitely be introduced earlier in high school, like we could introduce maybe more coding based classes or who knows, [even] fashion,” Arslan said.

In core classes like math, Koy says students have to remember that their frustrations are part of a “mental marathon,” and that although they may never need to find X at the grocery store, their class experiences do build their character.